‘Reprise’ REVIEW: A sterling sketch of life’s what-ifs and could-have-beens – with a French New Wave kink

‘Reprise’ REVIEW: A sterling sketch of life’s what-ifs and could-have-beens – with a French New Wave kink

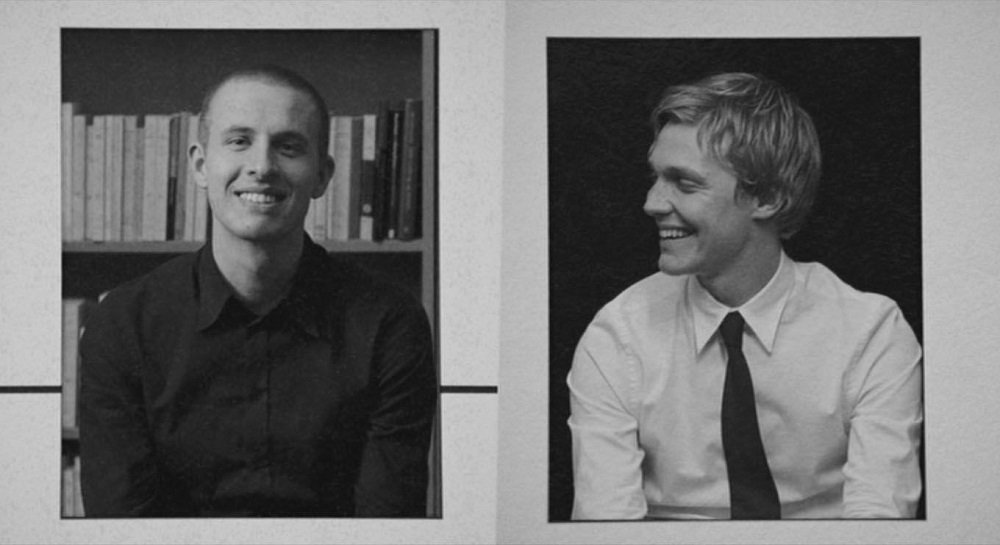

Anders Danielsen Lie stars as Phillip in Reprise, directed by Joachim Trier. Photo courtesy of MUBI.

When the name of Danish-Norwegian cinéaste Joachim Trier is mentioned, perhaps the most immediate thing that comes to a cinephile’s mind is his Oscar-nominated romantic dramedy The Worst Person in the World, especially when recency bias factors in. Set in the capital of Norway, the film is the third installment in Trier’s informal “Oslo Trilogy,” but moviegoers often overlook the director’s 2006 debut feature Reprise – the first piece in the film series.

Reprise conveys neither the nihilism of Oslo, August 31st, nor the dark hilarity of The Worst Person in the World, yet its frenetic and poignant cadence makes it a distinct work on its own. It’s a welcome departure from its successors that even if we decide to watch the trilogy in a nonlinear order, it doesn’t rob us of a meaningful viewing experience.

At the heart of the film are longtime Oslovian pals Erik (Espen Klouman Høiner) and Phillip (Anders Danielsen Lie) as they cruise into their early twenties as writers hungry for success. The story opens with the two friends in what seems like a career-defining moment of dropping their first manuscripts into a mailbox in the hopes that a publisher will find interest in it. Then an unknown narrator transports us swiftly into a whirlwind sequence of what-ifs and could-have-beens mounted through an impressive montage à la François Truffaut’s Jules and Jim.

Matched by Olivier Bugge Coutté’s clever editing alongside Ola Fløttum and Knut Schreiner’s glorious musical score, Trier wears this French New Wave trick, this devil-may-care storytelling, as a badge throughout the 105-minute runtime of Reprise. His ambition for this film parallels those of his characters. But make no mistake, the director doesn’t rely on this avant-garde technique to solely display his cinematic arsenal or add flair to the mise-en-scène because, if anything, it acts as a hook to which the narrative is anchored, accenting how life is easier imagined than lived and how it has its cunning ways of taking us by surprise. Even the unseen narrator lends the film an interesting texture.

The official poster of Reprise.

But technique can only go so far, no matter how exciting it may seem. The good thing is Trier knows not to overstay his welcome and manages to strike a lucid balance between his visual kinks and the viewer’s pleasure, tapping into the film’s emotional core that hinges on the rewarding rapport of its lead actors. Høiner creates a pulsating and sober performance out of Erik that implores us to root for him, especially when we learn that his manuscript fails to make it – a humbling rite of passage for most artists and writers – unlike his best pal who leaps into becoming a breakout writer after the publication of his debut novel but not without a repercussion as he struggles with psychosis following a tumultuous romantic relationship with the pensive Kari (Viktoria Winge). Danielsen Lie’s Phillip exudes a raw and enigmatic emotion that is very specific to the Norwegian actor’s brand of acting – the most satisfying of which is his Anders in Oslo, August 31st – as if his face is made for cinema. He knows when and how to pull the trigger, and when he does, it will gently unclog our tear ducts.

Our protagonists are flawed but in a manner that benefits the narrative more than ruins it. In fact, both of them possess this breed of narcissism and machismo that informs us of the social background to which these characters belong. It’s not an overstatement to say that a certain privilege must be at work for one to pursue their literary ambitions without having to deal with the material reality that comes with it.

The pesky machismo also extends to the environment surrounding our protagonists, particularly to their small circle of all-cis-male, punky friends, who pay little heed to whether or not they offend someone. This is part of the reason why Erik secludes his girlfriend Lillian (Silje Hagen) from them in fear that they might not vibe with her, yet he continues to tolerate his friends’ toxic behavior. Despite these Upper West Side-y tendencies that permeate the film, Trier’s direction and his writing collaboration with longtime friend Eskil Vogt engineer a level-headed empathy, allowing us to resonate with what these impulsive young adults are going through. Surprisingly, Trier does it without killing his darling, contrary to (pardon the spoiler) what he would later do with Danielsen Lie’s characters in the succeeding films of the trilogy.

A shot from the film’s opening montage.

If revisited, only a viewer with a discerning eye can surmise that the “Oslo Trilogy” is an intimate study of the metropolis – as both a source of suffering and respite – and the human relationships that either prosper or wither in it. The city anchors the motivations, doubts, and apprehensions of Trier’s characters, who, by fate or by chance, are forced to confront the quiet turbulence of their lives that Trier crafts. This is where I find the trilogy most liberating – a miracle of cinema that simply deserves to be seen and gushed over.

In Reprise, amidst the hypnotic yet seemingly decaying landscape of Oslo and Paris, uncertainty is the most terrifying thing in the world, especially for twenty-somethings. It then holds water that the film is replete with persnickety alterations and reimaginations of the fragmented past and future in an attempt to make sense of the ever-volatile present but to little avail.

“The only thing left is everything,” Phillip says. But, in this realm that Trier builds, everything is bound to change. Careers falter. Relationships go astray. Love saturates. Passion fades. Could it be the reason why Phillip recklessly toys with fate every time he counts down from ten to determine what will happen to him next, even at the expense of his own life? We’ll never know for sure. I suppose that is the point.

In the end, we’ll continue to devise a plan despite our gnawing awareness that it may fail. And when it does, we’ll create a new one and another and another and another. Reprise tells us that sometimes life doesn’t turn out the way we intend it to. But it’s okay. It has to be. And somehow, we’ll carry on. Perhaps, every time we feel that our world is about to collapse, all we need is a reprise, by which I mean the courage to try again.

Reprise is now streaming on MUBI.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lé Baltar is a writer, poet, and film critic. They are secretary of the Society of Filipino Film Reviewers (SFFR). Their articles have been published in Film Police Reviews, SINEGANG.ph, Philippine Collegian, Tinig ng Plaridel, and Vox Populi PH, while their poems have appeared in local and international literary spaces. They study journalism in UP Diliman.